Cuba takes a zero-tolerance stance on illicit drugs, vowing even to “fight drugs with blood and fire.” The drug policy appears to have been successful. Cuba has one of the lowest homicide rates in the western hemisphere, along with some of the lowest reported rates of illicit drug use, production, and transit. These accomplishments are unique in a region greatly affected by drug-related violence. They are also confusing.

Evidence increasingly shows that zero-tolerance approaches towards drugs like prohibition and punitive sanctions have contributed significantly to insecurity, violence, corruption, displacement, and a host of public health issues in Latin America and the Caribbean. Why hasn’t Cuba’s hard-line on illicit drugs yielded the same results? Will Cuba remain insulated from the costs of prohibition as it continues to open its doors to the international community?

Isabella Bellezza-Smull, the new Latin America & World Reality Tours Coordinator at Global Exchange, previously lived in Rio de Janeiro where she worked with the Igarapé Institute on drug policy reform. Her report Will Cuba update its drug policy for the twenty-first century? traces the country’s policy towards illicit drugs from the 1959 revolution to present. It discusses emerging challenges the island faces as it undergoes domestic reforms that allow for increased access to illicit substances. Isabella notes that Cuba has a unique opportunity to avoid the mistakes other countries have made in past decades by preventatively exploring alternative, proven approaches to drugs like harm-reduction, the decriminalization of use and possession, alternatives to arrest for low-level dealers and producers, and even the legal regulation of certain drugs like marijuana.

Her work was picked up by the Brazilian newspaper O Globo. Here is the transcribed interview:

Can we say that Cuba has been spared from the drug war and its harmful effects that we see in several countries around the world? How reliable are the Cuban government’s claims that the country does not have a drug problem?

In general term, yes, Cuba has been spared from the drug war. From the metrics available, we see that Cuba has one of the lowest homicide rates in the region, as well as very low rates of drug use, production and trafficking. These indicators have been corroborated by the US State Department over the past decades in INCSR reports [International Narcotics Control Strategy Reports]. And State has not easily bestowed praise onto Cuba given the historically fraught relationship, which helps confirm the reliability of these figures.

What has made Cuba such a unique case in the region, perhaps in the world? What have been the factors protecting the country from the plague of drugs, and how can Cuba’s progressive political and economic openings make them a problem?

Cuba has a very unique national context. State-sponsored universal access to education and health services are rightly considered to be crown jewels of the revolution. They’ve produced enviable results. Achievements like universal literacy, the dramatic reduction of certain diseases like HIV/AIDS, universal access to safe drinking water and basic public sanitation. Cuba also has one of the region’s lowest infant mortality rates and longest life expectancies. So Cuba has very successfully built a culture of health.

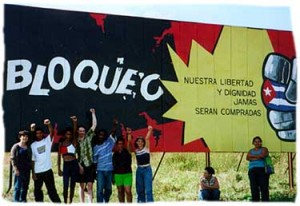

But the country has also been very isolated in economic terms — it has had limited engagement in international markets, which has hindered the entry of drugs and recreational drug cultures. And domestically, the conditions for drug sales have been poor given very low disposable incomes, largely due to the US economic embargo, but also because of the virtual absence of a private sector. But these conditions are gradually changing. Cuba has opened to the world slowly but surely since the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. And we see that with every opening, the Cuban government has been increasingly concerned about drugs. The drug issue is still relatively benign in Cuba, especially in comparison to neighboring countries, but it’s important to see how the situation develops.

Given Cuba’s current drug situation and the recent move towards more progressive approaches elsewhere that move beyond simple prohibition and repression, could Cuba become a laboratory of what might have happened — or can still happen — in other countries if they had adopted policies such as decriminalization, legalization or regulation of the drug market and harm reduction?

Certainly Cuba has the opportunity to get it right by moving away from prohibition and punitive sanctions, towards proven public-health-driven alternatives. So, the question is how the country will deal with the expected increased consumption, production, and drug trafficking. As is common, the Cuban government has publicly adopted a hard-line. The Cuban National Drug Commission in June of this year reaffirmed its commitment to fighting illicit drugs, but there is an important debate within the public health sector about how to approach increasing illicit drug use. And this is very encouraging because they’re questioning the traditional model of abstinence and “just-say-no” (to drugs). They are realizing that there are people who do not, or cannot, stop using drugs outright and that demanding abstinence should not be a precondition for treating or consulting them. This is in line with a harm reduction approach to drug use — focusing on the prevention of harm, rather than on the prevention of drug use, itself.

Could this reiterated conservative view of the Cuban government on drugs lead the country to lose this opportunity to deal with the problem more effectively?

Yes, this is a risk and it is something to be seen.

Although some protective factors against the drug problem in the last decades are changing, such as disposable income and access to substances, others will probably continue the same, such as the high level of education of the population and a solid system of public health. Can this also help “guide” the country toward more progressive and efficient drug policies?

Definitely, but again it will be a question of how the Cuban government goes about educating a new generation of Cubans about drug use. Education and prevention campaign discourse continues to be rooted more in “say-no” and abstinence than on complete, honest information about the effects and impacts of the use of certain drugs, particularly currently illegal ones like marijuana. If this continues, a new generation of Cubans experimenting with drugs could find that they can be used recreationally, because not all drug use is problematic. And this would create a discrepancy between what the Ministry of Education is teaching and what Cubans are experiencing, undermining the abstinence prevention discourse.

Will we then see a kind of denial, a discourse that drugs and their consumption are counter revolutionary things, a problem of bourgeois capitalist societies?

Yes, there may be a continuity of the rhetoric that there are no illicit drugs in Cuba, which is not entirely true, and that drug use is antithetical to revolutionary consciousness building. If the government is realistic about the existence of drugs in open societies, it will preventatively adopt new approaches tested elsewhere as it opens its doors. These could include decriminalizing the possession of all drugs for personal use, adopting harm reduction strategies, and elaborating alternative sentencing procedures for nonviolent drug offenders, including low-level traffickers and producers.

Furthering the

Furthering the

Take Action!

Take Action!