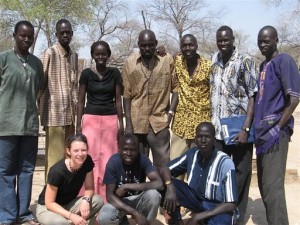

Photo Credit: Beth Garriott

On July 9, 2011, South Sudan gained independence from Sudan after an overwhelming majority of South Sudanese voted to secede and become Africa’s newest country.

Beth Garriott, Global Exchange’s Gifts & Grants Officer, lived in South Sudan from 2006-2007 while she worked with Mercy Corps. She shares her thoughts about South Sudan’s independence.

The birth of a New Nation: South Sudan

Photo Credit: Beth Garriott

“Peace is good. I built a house a year ago, and it has not been burned down like it was every year before.” —Nuer woman, Rumbek, South Sudan – 2006, one year after the Comprehensive Peace Agreement was signed

Watching the celebrations in South Sudan this weekend, I felt a mix of emotions. Mostly I felt incredible joy, relief and satisfaction on behalf of millions of people who had endured more loss and pain than most could ever imagine – after a generation of civil war and the displacement of millions of people. I also couldn’t help but feel a longing to be back in Sudan, celebrating with the friends I made during my time in the country from 2006-2007. And I was cautiously optimistic about the future of this infant nation, given continued conflicts along the border regions between the north and the south, tensions among tribes in the south over land rights and political control, and the poor infrastructure, healthcare options and education system in the country.

Photo Credit: Beth Garriott

That said, sheer delight trumped all other emotions and questions this past weekend while I watched the singing, dancing and festivities online. A world away, I share in their joy. But my happiness about South Sudan’s independence surely didn’t come close to comparing to the utter elation that most people in the country – and South Sudanese around the world – must have been feeling, deep in their bones, on July 9th.

Photo Credit: Beth Garriott

South Sudan is different culturally and religiously from the northern part of the country – it is primarily Arab and Muslim in the north and animist and Christian in the south.

For far too long the people of South Sudan were oppressed. They suffered through violence, displacement and slavery during 22 years of civil war leaving over one million people dead and more than four million people displaced. But finally, in 2005, they got a chance to taste freedom when the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) was signed, signaling the start of a six-year semi-autonomous period in which the government of South Sudan would be initiated and power-sharing structures would be established with the North. At the end of the six years, the CPA stipulated that South Sudan would have a chance to vote for independence.

Photo Credit: Beth Garriott

During my time in South Sudan working for a U.S-based non-governmental organization on an initiative to strengthen civil society, most people were not certain whether peace would even last another year, much less all the way through to the election in 2011. One of the least developed countries on earth, the majority of people in South Sudan back then had no access to clean drinking water, electricity or roads. I lived in a mud hut and had it well.

Photo Credit: Beth Garriott

Carrying out an election in such a massive geographical area (the former country of Sudan was roughly the size of Western Europe, the largest country in Africa) without roads, and with a literacy rate of between 20-30%, seemed all but impossible. Additionally, tensions were still high between the northern and southern militaries, and rising between various tribes in South Sudan over land and political representation. But alas, we were all proven wrong when – in January this year – democracy triumphed on a continent where peaceful elections are few and far between. And this past weekend, the long and perilous journey towards a freer and calmer Sudan was complete.

Photo Credit: Beth Garriott

My time in South Sudan was the most seminal and important period of my life. It continues to inspire and ground me in my work at Global Exchange to bring about greater awareness of human and environmental rights issues around the world. If I close my eyes, I can still picture the lush mango trees along the Nile River in Juba, the new capital of South Sudan. I smile imagining the traditional Dinka greeting, which includes a brief clasping of a person’s right hand, then slapping of the other’s shoulders with the same hand – over and over again for several cycles.

Photo Credit: Beth Garriott

I recall the conversations I had with community members in the remote village where I worked for a year – in the disputed region of Abyei, straddling the north-south border – where much of the country’s oil lies (it is unclear whether this small area will become a territory of North or South Sudan). People here talked about their vision for South Sudan – a peaceful, independent and thriving nation.

This vision is now two-thirds of the way there.