It has been established beyond a doubt that if Trayvon Martin were a young white boy with a bag of skittles and an iced tea he’d still be alive today. He would not have been seen as “suspicious” in a gated community, his clothing wouldn’t be a marker of being “up to no good” and his skin color wouldn’t signal “danger” and provide a cultural, and in Florida, legal justification for fear.

As Michelle Alexander, author of “The New Jim Crow” put it, “… if he had been white, he never would have been stalked by Zimmerman, there would have been no fight, no funeral, no trial, no verdict. It is the Zimmerman mindset that must be found guilty – far more than the man himself.

It is a mindset that views black men and boys as nothing but a threat, good for nothing, up to no good no matter who they are or what they are doing. It is the Zimmerman mindset that has birthed a penal system unprecedented in world history, and relegated millions to a permanent under-caste.”

Though African-Americans make up less than 14% of the population of the United States, they make up more than 40% of the prison population and there are now more black men in prison than there were slaves in 1850.

Trayvon Martin’s death is more than a tragedy for one family, as deep and as profound as that is, it is an indictment of a state that accepts gun ownership, concealed weapon carry laws and Stand Your Ground laws. The tragedy is also an indictment of our country where fear of black boys and men is legitimated by law and portrayed as “normal”.

Trayvon Martin rally in San Francisco, July 2013

As our communities become more polarized and fearful, they become the tinder ready to burn when the spark of easy access to guns is introduced. When the Second Amendment becomes the cover for that fear, and when the government-led drug war becomes the means to separate and segregate our population by filling our jails, tragedy is inevitable.

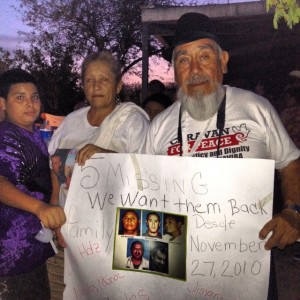

This is a tragedy that is all too well-known by our neighbors in Mexico where impunity, fear and easy access to guns have created a situation leading to this staggering statistic – 70,000 people have died and tens of thousands are missing – people whose families mourn with the same deep grief that you see in the faces of Trayvon Martin’s parents.

I have sat with parents whose loss is engraved in the lines on their faces just as it is seen in the faces of Sybrina Fulton and Tracy Martin; it is a grief that seems to scream out how incomprehensible it is that this young person is now gone forever – for no reason. And it is a grief that challenges us all to take on new roles as mothers, friends and neighbors to end the violence.

Mexican Poet & Activist Javier Sicilia

Last summer, the Mexican poet, Javier Sicilia, who also lost a son to violence, led a month-long, U.S. coast-to-coast Caravan for Peace – visiting 29 cities, calling for new federal legislation to regulate guns and for a dialogue about solutions to the drug war that won’t separate and divide communities with tragic consequences.

Caravan for Peace travelers

The Caravan travelers – more than a hundred victims of drug war related violence in Mexico – met with victims of violence in the U.S. and they were eager to make connections to the communities most affected by the war on drugs, by the violence of our gun culture and by mass incarceration. In Mexico, most gun crimes are committed with weapons bought legally in the United States and smuggled into Mexico. The roots of Mexico’s drug violence are complex, but lax U.S. gun laws make it easy for Mexican cartels to get guns and escalate the killing, sometimes the killings are targeted but often they are random and incomprehensible.

A cell phone conversation between Michelle Alexander and Javier Sicilia on a dusty back road in Alabama led to a deep and respectful friendship between the two great thinkers. Listening to them talk, I realized that as mother and as an activist, they provide me a framework for understanding what is happening that doesn’t allow for despair but demands action.

“We want to share solutions, not tragedy. As neighbors, we ask for your help,” said Javier. I believe, in turn this international solidarity will help us to see the craziness of arming a fearful public which has been taught to profile rather than understand.

This fall, the Voices of Victims speaking tour will, once again, come to the U.S. to help us connect the dots about the causes of violence, the inadequacies of our gun and drug laws and to put faces of grief and action to the terrible statistics. Starting in Denver, Colorado on October 23 at a meeting on drug policy reform and ending on November 15 in Jackson Mississippi with Michelle Alexander, the tour hopes to build a movement strong enough to honor the memory of the fallen sons and build a movement capable of delivering true justice.

President Obama has called for the same. Speaking shortly after the Zimmerman verdict, he said:

“I now ask every American to respect the call for calm reflection from two parents who lost their young son. And as we do, we should ask ourselves if we’re doing all we can to widen the circle of compassion and understanding in our own communities. We should ask ourselves if we’re doing all we can to stem the tide of gun violence that claims too many lives across this country on a daily basis. We should ask ourselves, as individuals and as a society, how we can prevent future tragedies like this. As citizens, that’s a job for all of us. That’s the way to honor Trayvon Martin.“

Mourn and Organize!

TAKE ACTION!

TAKE ACTION!

Help stem the flow of guns and ammunition across the border by signing this petition today.