The following video originally aired April 20th on GRITtv. In it, Shannon Biggs & Maude Barlow speak about recognizing the Rights of Nature:

—

The following video originally aired April 20th on GRITtv. In it, Shannon Biggs & Maude Barlow speak about recognizing the Rights of Nature:

—

This piece was originally sent to our Freedom from Oil list. Be the first to receive news updates and action items by signing up for our e-mail lists.

One year ago today the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig exploded off of the coast of Louisiana killing eleven men and igniting the largest oil disaster in U.S. history.

To mark the one-year anniversary, I released Black Tide, and joined Gulf Coast residents harmed by the disaster at BP’s annual shareholder meeting in London and at PowerShift in Washington, DC.

I have shared the statements of those who could not attend these events, including Keith Jones, whose son Gordon died aboard the Deepwater Horizon.

I appeared on Democracy Now!, BBC, NPR and other shows and have written several articles, including “Questions for BP and the oil industry, one year after Deepwater Horizon,” for the Harvard School of Journalism.

As BP spreads its wealth to the GOP, we are spreading the message that the one-year anniversary is THE moment to remind the nation and the world that the Gulf oil disaster is not over and that fundamental change is still needed to ensure such a disaster never occurs again.

Please Join Us!

TAKE ACTION

Support local actions in the Gulf Coast with the Gulf Restoration Network as they Declare: “The Oil is Still Here and So Are We!”

Take Action where you live TODAY with Act Against Extraction Day of Action April 20!

I’m still on tour! Please join me at a city near you, share my events with friends, and keep spreading the word.

Thank you.

This article originally appeared on AlterNet.

It is time to learn the lessons of the disaster: neither the technology nor the regulation of deepwater drilling is capable of protecting workers or the environment.

One year ago this month, the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig exploded 50 miles off the coast of Louisiana. This week we learned that the company’s CEO, Steven Newman, and other executives of Transocean, the owner and operator of the rig, were not only awarded raises, but also millions of dollars in bonuses for 2010 after “the best year in safety performance in our company’s history,” according to the company’s annual report and proxy statement.

News of the bonuses went viral and enraged the public. Within one day, announcements that the executives were donating the bonuses to families of the 11 men who died on the rig soon went viral as well.

While the contributions are certainly welcome, they are little more than a gesture. First, the contributions accounted for but a small fraction of the total bonuses the executives received (approximately $250,000 out of nearly $900,000, according to Fortune), and not a single executive turned down his or her raise.

The fact that Transocean awarded the raises and bonuses is more than an affront to the families and colleagues of the 11 men who died aboard the rig and the millions more who have suffered as a consequence of the 210-million-barrel oil gusher. They are also a warning.

Transocean is the largest deepwater driller in the world, operating nearly half of all rigs in more 3,000 feet of water in the Gulf of Mexico. All of the major oil companies rely heavily upon its services. If the ongoing fight for new offshore drilling in places like California (where I live) is lost by opponents, Transocean will unquestionably enter these new waters. Yet, investigations are sure to conclude that Transocean’s operational failures are as much to blame for the Deepwater Horizon disaster as are BP’s flawed managerial decisions. If Transocean has not learned the lessons of the largest oil disaster in American history, then we all have great reason to worry.

Since 2008, 73 percent of incidents that triggered federal investigations into safety and other problems on deepwater drilling rigs in the Gulf have been on rigs operated by Transocean, according to the Wall Street Journal.

“This event was set in motion years ago by these companies needlessly rushing to make money faster, while cutting corners to save money,” Stephen Lane Stone, a Transocean roustabout who survived the April 20 explosion, told a Congressional committee last May. “When these companies put their savings over our safety, they gambled with our lives. They gambled with my life. They gambled with the lives of 11 of my crew members who will never see their families or loved ones again.”

The results of that cost cutting were apparent all across the Deepwater Horizon — a rig leased by BP and run by Transocean. Of the 126 people on board the rig on April 20, 79 worked for Transocean. More tragically, of the 11 men who died that day, nine were Transocean employees.

Testimony from federal investigations reveals charges of literally hundreds of unattended repair issues on the Horizon. Transocean chief electronics technician for the rig, Mike Williams, described one as “the blue screen of death,” explaining that the computer screens regularly “locked up” with no data coming through, making it impossible for the drillers at those chairs to know what was happening in the well 18,500 feet below.

Williams also reported the failure to utilize the automatic alarm systems. On April 20, as gas rose from the Macondo well into the rig, the crew should have been automatically alerted and operations in their areas automatically shut in. Instead, the automatic gas alarms were intentionally inhibited, set to record information but not to trigger alarms.

More than a year before, Williams asked why. His superiors replied that they did not want people woken up “at three o’clock in the morning due to false alarms.” When Williams tried to fix the alarms, Transocean subsea supervisor Mark Hay reportedly told him, “The damn thing’s been in bypass for five years. Why did you even mess with it?” Hay said, “Matter of fact, the entire [Transocean] fleet runs them in bypass.”

Even without the alarms, the blowout preventer (BOP) should have shut in the well. But when the engineers in the drill room triggered it, the BOP failed to activate.

The rig has two additional backups. The first, the Emergency Disconnect System (EDS), triggers the BOP and separates the rig from the wellhead. The EDS was activated by the crew on the bridge, but again, nothing happened.

Federal regulations require BOPs to be recertified every five years. The Deepwater Horizon BOP had been in use for nearly 10 years and had never been recertified. Getting it recertified would have required Transocean to take the rig out of use for months while the four-story stack was disassembled and examined.

There were several problems with the BOP that were well known on the rig and had been reported in the BP Daily Operations Reports as early as March 10. Both BP and Transocean officials knew the BOP had a hydraulic leak. They also knew that federal regulations required that if “a BOP control station or pod … does not function properly,” the rig must “suspend further drilling operations” until it’s fixed.

When the BOP failed to activate from the floor and from the bridge, there should have been one more backup, the automatic mode function (AMF), but it failed, too. The reason, according to BP, is that the batteries had run down.

All across the Deepwater Horizon, the technology on which everything so dearly depends was failing, and with catastrophic results.

Rather than overhaul its safety system, Transocean declared that in 2010 “we made significant progress in achieving our strategic and operational objectives for the year,” but unfortunately, “these developments were overshadowed by the April 20, 2010 fire and explosion onboard our semi-submersible drilling rig, the Deepwater Horizon.”

Unfortunately, the public has allowed the events aboard the Deepwater Horizon and all that followed its explosion to be overshadowed as well. As we approach the one-year anniversary, it is time to learn the lessons of that disaster: that neither the technology nor the regulation of deepwater drilling is capable of protecting the workers on the rigs, the ecosystems within which they work, or those whose livelihoods are dependent upon those water ways and beaches.

As oil industry analyst Byron King has said, “We have gone to a different planet in going to the deepwater. An alien environment. And what do you know from every science fiction movie? The aliens can kill us.”

On April 20, 2010, the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig — leased by BP and owned by Transocean — exploded off the coast of Louisiana, killing eleven men, and unleashing a 210 million gallon oil gusher. It became the largest oil disaster in American history, and it could happen again.

Today, we have learned that BP may renew drilling on ten different wells in the deepwaters of the Gulf of Mexico as early as this summer, and that Transocean’s executives were awarded millions of dollars in bonuses after what the company described as “the best year in safety performance in our company’s history.”

We believe that it is time for change.

To mark the one-year anniversary of the disaster, we will release Black Tide: the Devastating Impact of the Gulf Oil Spill (Wiley), by Global Exchange Energy Program Director, Antonia Juhasz.

Black Tide is based on hundreds of personal interviews Antonia conducted during her time spent embedded within those communities most impacted by the disaster. It is a searing look at the human face of this tragedy.

Naomi Klein, author of The Shock Doctrine, says of Black Tide:

“These remarkable stories—of loss, heroism, and culpability—are a vivid reminder that this catastrophe will be with us for decades.”

The Black Tide book tour begins on April 9 in San Francisco. The next day, Antonia heads to London with Gulf Coast residents harmed by the disaster for BP’s annual shareholder meeting, before launching a national tour taking her across the U.S. and to a city near you.

The Global Exchange Energy Program is committed to exposing the true cost of our deadly oil addiction on real people, real communities, and real ecosystems at all points of oil’s operations as we work to promote the transition to renewable energy.

We hope you will join us and help us spread the word!

GET INVOLVED

It’s official; the White House announced earlier today that the moratorium on deep water drilling which was not set to expire until November 30th is now being lifted. The announcement was made by Interior Secretary Ken Salazar during a conference call with reporters Tuesday afternoon. Salazar explained:

“We have made and continue to make significant progress in reducing the risks associated with deepwater drilling” and therefore, “I have decided that it is now appropriate to lift the suspension on deepwater drilling for those operators that are able to clear the higher bar that we have set.”

Global Exchange is deeply disappointed by this decision to prematurely lift the ban. Antonia Juhasz, Global Exchange Energy Program Director, explained in a recent article:

IT SHOULD BE BLATANTLY CLEAR at this stage of the Deepwater Horizon tragedy that we are witnessing the failure of an entire system, rather than of one operator. Systemic solutions are therefore required. One obvious first step is a permanent moratorium on all offshore drilling—a model of energy extraction which the industry is unable to safely perform and the government is unable to adequately regulate.

Upon hearing the news about the drilling ban being lifted, Antonia had this to say (while in Alabama via phone, researching for her new book on the Gulf oil disaster🙂

One very positive step of the Obama administration was putting in place a deeply needed moratorium on deep water drilling, but it seems that election year politics have led to a quid pro quo in which the administration implemented extremely limited regulations on offshore drilling in exchange for an early lifting of the moratorium.

Environmental groups have been quick to respond to today’s announcement.

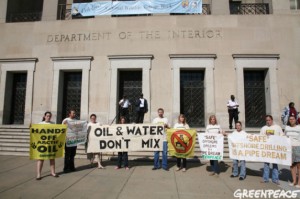

Sierra Club issued a press release on their website stating “The BP disaster was a wake up call, but our leaders keep hitting the snooze button.” Greenpeace included a link to “Tell Congress: No New Drilling. Period” along with photos of their protest today.

The moratorium on deep water drilling was originally imposed on May 27th before a revised ban was enacted on July 12th and set to expire November 30th.

If you’re concerned about the ramifications of this early ban lifting, here are a few ways to take action and make your voice heard:

Tell Congress No New Drilling: Visit Greenpeace for an easy-to-fill-out form.

Call or email the White House: White House phone #s and email are here and here.

Interior Secretary Ken Salazar. Photographer: Mark Wilson/Getty Images

The following post is cross-listed on the Chevron Program blog:

It’s official; the White House announced earlier today that the moratorium on deep water drilling which was not set to expire until November 30th is now being lifted. The announcement was made by Interior Secretary Ken Salazar during a conference call with reporters Tuesday afternoon. Salazar explained:

“We have made and continue to make significant progress in reducing the risks associated with deepwater drilling” and therefore, “I have decided that it is now appropriate to lift the suspension on deepwater drilling for those operators that are able to clear the higher bar that we have set.”

Global Exchange is deeply disappointed by this decision to prematurely lift the ban. Antonia Juhasz, Global Exchange Energy Program Director, explained in a recent article:

IT SHOULD BE BLATANTLY CLEAR at this stage of the Deepwater Horizon tragedy that we are witnessing the failure of an entire system, rather than of one operator. Systemic solutions are therefore required. One obvious first step is a permanent moratorium on all offshore drilling—a model of energy extraction which the industry is unable to safely perform and the government is unable to adequately regulate.

Upon hearing the news about the drilling ban being lifted, Antonia had this to say (while in Alabama via phone, researching for her new book on the Gulf oil disaster:)

One very positive step of the Obama administration was putting in place a deeply needed moratorium on deep water drilling, but it seems that election year politics have lead to a quid pro quo in which the administration implemented extremely limited regulations on offshore drilling in exchange for an early lifting of the moratorium.

Environmental groups have been quick to respond to today’s announcement.

Sierra Club issued a press release on their website stating “The BP disaster was a wake up call, but our leaders keep hitting the snooze button.” Greenpeace included a link to “Tell Congress: Now New Drilling. Period” along with photos of their protest today.

The moratorium on deep water drilling was originally imposed on May 27th before a revised ban was enacted on July 12th and set to expire November 30th.

If you’re concerned about the ramifications of this early ban lifting, here are a few ways to take action and make your voice heard:

Tell Congress No New Drilling: Visit Greenpeace for an easy-to-fill-out form.

Call or email the White House: White House phone #s and email are here.

(This article was originally posted on Huffington Post.)

“The fish are safe,” declared LaDon Swann of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. This should have been good news to the audience at Alma Bryant High School in Bayou La Batre, Alabama.

“The fish are safe,” declared LaDon Swann of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. This should have been good news to the audience at Alma Bryant High School in Bayou La Batre, Alabama.

Virtually all of the 150 people attending the August 19 community forum made their living in one form or another in the Alabama fishing industry, and most had for generations, until the explosion of the Deepwater Horizon.

Having spent four months with a severely reduced, or nonexistent income, all are now desperate. Even the lucky few able to participate in BP’s Vessels of Opportunity (VOO) program are now largely out of work as BP has all but shut down the program in the area. Many can no longer afford rents or mortgages, pay medical bills, or even, in growing numbers, provide food for their families.

Even so, none appeared relieved at Swann’s words. They simply did not agree with him, as far too many continue to see far too much evidence that both oil and dispersant remain in their waters. As scientists at the University of Georgia concluded on August 17 using the federal government’s own data, as much as 79% of the 4.1 million barrels of oil BP spilled in to the Gulf “remains in the Gulf in varying forms of toxicity.”

Less then 24 hours later, in a small boat captained by Pat Carrigan, we encountered an oil slick within 15 minutes of setting off from Carrigan’s backyard on Dauphin Island. We were in the Mississippi Sound heading toward the Katrina Cut, a shortcut to the Gulf of Mexico opened when the storm split one portion of Dauphin Island off from the rest of the island five years earlier.

“That’s dispersed oil,” Carrigan said as we passed through a slick of light brown foamy goo. Carrigan has fished these waters for more than 20 years and is a former VOO worker. Glint Guidry, Acting President of the Louisiana Shrimp Association, shared Carrigan’s assessment. Looking at a photograph of the slick I showed him the following day, Guidry said, “That’s oil, oil with dispersant.”

The shrimpers view the slick as cause for concern because these waters were reopened to shrimping on August 8.

But, as LaDon Swann had reminded the audience at Alma Bryant, the federal government and Gulf States have established specific protocols for re-opening these waters to fishing.

These protocols state that the visual observation of oil or “chemical contaminants” on the surface of the water is cause for the recommendation that the fishery be closed “until free of sheen” for at least 30 days in federal waters and seven days in Alabama state waters.

“These waters should be filled with shrimpers,” Carrigan explained to us on the August 20th trip. Instead, there was not a single boat on the water shrimping during the several hours of this trip. “They’re just not shrimping.”

And the oil was not limited to the water.

After passing through the sheen of dispersed oil, his passengers were more than a little disconcerted when Carrigan took off his shirt and jumped into the water to pull the boat ashore as we landed at a western strip of Dauphin Island accessible only by boat. We were even more concerned when he told us to do the same as we disembarked.

After trekking through a completely untouched and unpopulated strip of wild brush, green grass, and blue flowers, we came upon a landscape opened to clear blue sky, white clouds, and a stunning white sandy beach.

Rocky Kistner of the Natural Resources Defense Council, who had arranged for the trip, looked ecstatic as he gazed at the beach — that is, until he looked down.

Huge tar balls, some as large and as thick as an outstretched hand, stretched in a line where the waves had left them, as far as the eye could see down the beach.

A baby’s sippy cup lid covered in tar sat in a bed of white sand. A Dawn dishwashing soap bottle lay covered in the sticky goo. Using a piece of bark he found on the beach, Zach Carter of Mobile’s South Bay Community Alliance bent down and started scooping tar balls into a white bucket.

“It’s not only on the beach, it’s in the water,” Carrigan said, looking stricken. He stood in the ocean, bent down, gathering more tarballs in his hands as they washed up.

Most disturbing was that the beach, accessible only by boat, was deserted. “There used to be BP workers up and down this beach cleaning it up, constantly,” Carrigan said. “Now, nothing. Just oil.”

Photos by Sandy Cioffi and Greg Westhoff (please do not reprint without photo credit)

This article originally appeared in the August 2010 issue of Progressive Magazine, The Big Spill.

IT SHOULD BE BLATANTLY CLEAR at this stage of the Deepwater Horizon tragedy that we are witnessing the failure of an entire system, rather than of one operator. Systemic solutions are therefore required. One obvious first step is a permanent moratorium on all offshore drilling—a model of energy extraction which the industry is unable to safely perform and the government is unable to adequately regulate.

In the last five years alone, there have been, just in the Gulf of Mexico, 400 offshore safety and environmental incidents, including blowouts and other major accidents, according to a Houston Chronicle analysis. BP is the leader with forty-seven violations, Chevron is second at forty-six, and Shell is third at twenty-two.

Among the unifying features of these incidents is the failure of the U.S. Minerals Management Service to act. The MMS failed to travel to one-third of the accident scenes, collected only sixteen fines out of 400 incidents, and did not investigate every blowout, as their own rules require.

Transocean, the company that owned and operated the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig, is another common thread. Transocean is the largest deep-water driller in the Gulf of Mexico, operating nearly half of all the rigs in the Gulf that work in more than 3,000 feet of water. It is the company of choice for industry leaders, including Chevron and Exxon, even though, according to a recent Wall Street Journal analysis, nearly three of every four incidents that triggered federal investigations into safety and other problems on deepwater drilling rigs in the Gulf since 2008 have been on rigs operated by Transocean.

The companies also all use the same grossly negligent subcontractor, the Response Group, to write their disaster “preparedness” plans for their Gulf operations. On June 15, Congressman Ed Markey, chair of the House Subcommittee on Energy and the Environment, revealed that all five of the major oil producers in the Gulf of Mexico—BP, Chevron, Exxon, ConocoPhillips, and Shell—used the virtually identical, tragically inadequate disaster plan on how they would handle a spill at their Gulf operations.

The plan, required by the MMS prior to approval for drilling, includes glaring errors and omissions that “vastly understate the dangers posed by an uncontrolled leak and vastly overstate the company’s preparedness to deal with one,” reports AP.

Three of the companies’ 2009 plans, including BP’s, listed as a consultant biologist Peter Lutz, who died in February 2005. Four ensured that their plans addressed the need to protect walruses, sea lions, and seals, although none of these live in the Gulf, revealing that the reports were not only cut and pasted between the companies, but also likely originally written for Arctic operations. Most importantly, the plans absolutely do not work, as BP’s response to the Deepwater Horizon explosion has made horrifically clear. Nonetheless, each and every plan received the government’s approval.

Perhaps more disturbing, however, is Markey’s response: token recommendations for lifting the liability cap on oil spills, requiring that oil companies pay more in royalties, implementing new safety reforms, and developing new technologies for capping wells.

In 1981, a federal moratorium on all new offshore drilling off the Atlantic and Pacific coasts and parts of Alaska was implemented. It was a direct response to the 1969 Unocal offshore oil rig blowout that released three million gallons of oil into the Santa Barbara Channel of California.

BP’s Deepwater Horizon tragedy is far worse, and far from an isolated incident. All around the world, every day, offshore rigs leak and spill. They far too often kill workers, release deadly toxins, produce methane, pollute the air and water, and destroy fisheries and livelihoods.

The oil industry has chosen to blatantly and disdainfully thumb its nose at the government’s regulatory authority, while the government has chosen to be an all-too-willing rubber stamp, demonstrating that it has neither the capability nor the will to regulate this industry. As it was in 1981, a moratorium is the only logical response.

Another key moment in U.S. oil history offers further solutions: the 1911 breakup of Standard Oil. The oil giant became too large for the government to regulate. In response to a massive people’s movement that built from the most local levels and reached the Supreme Court, Standard was broken into thirty-four separate corporate parts. Ultimately, the final step will come when we have retired the oil industry altogether once and for all.

Antonia Juhasz, author of “The Tyranny of Oil: The World’s Most Powerful Industry—and What We Must Do to Stop It” (HarperCollins 2008), is working on a book on the BP disaster. She is a director at Global Exchange, a San Francisco-based human rights organi- zation (www.TyrannyofOil.org,www.GlobalExchange. org/chevron).